Started in 2015, ”Pic of the Midday” is the second part of a project that focuses on different mountains via which Cecilia draws an analogy between them and (photographic) images. Of what is solid, immutable, static, monumental, calcareous or dusty to something liquid, fluid, mobile, dynamic, fragmentary and fleeting.

Playing with the meaning of the word ”Pic” –photo in English, and peak or mountain in French– Cecilia links ”picoftheday”, one of the most used hashtags on Instagram, with the Pic du Midi, a mountain in the French Pyrenees. In his essay ”Instagram as Non-Photography”, Mohammad Salemy (Kermanshah, 1967) examines the relationship between Instagram, and its ocean of images, with the concept of Non-Photography put forward by François Laruelle (Chavelot, 1937): ”Instagram photographs are not of the world but rather exist autonomously from it, engaged in a collective game of attention exchange”, and stresses: ”Like a responsive game, Instagram subjects photography to the mathematical network of users and their ”likes” and ”hashtags”, endangering the pictures’ symbolic meaning by instead emphasising their referential and contextual prominence.”

In fact, taking photos with, or for, Instagram implies refocusing one’s attention and entering another dimension, a mathematical dimension with its own specific logic that is nearly always estranged from the content and semiotics of the images. It has been estimated that, to date, Instagram has amassed over 40 billion photographs posted by users, in other words, 70 million photographs are uploaded every day to this image-based social network. A hashtag –or key word– has to be assigned to each of these elements within this ocean of algorithms or dematerialised photographs so that they can be classified and located quickly. The result is the creation of a seemingly arbitrary taxonomy, one that shifts the search experience to the mathematical arena.

In ”a certain Chinese encyclopaedia”, quoted by J.L. Borges in his text entitled ‘‘The Analytical Language of John Wilkins’’, animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camel-hair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies.’ This could well be the taxonomy of hashtags which, on the one hand, groups images in a subjective and improbably way and, on the other, reduces them to a single reading or endows them with clues to be interpreted which limit their polysemy. We might think, therefore, that using a taxonomy for images robs them of almost all of their meaning or diverts their essence to concepts unconnected to them. Tags tend to simplify their semantics and redefine the relationship between them and words.

With these ideas as her starting point, Cecilia offers a project in which she reflects on the concept of Non- Photography in the digital era and on the relationship between images and words, highlighting the huge amount of feedback that exists between the structures used to produce the images and the kinds of subjectivity that are dominant in neo-liberal culture that are often based on individualism, reinvention and personal self-fulfilment.

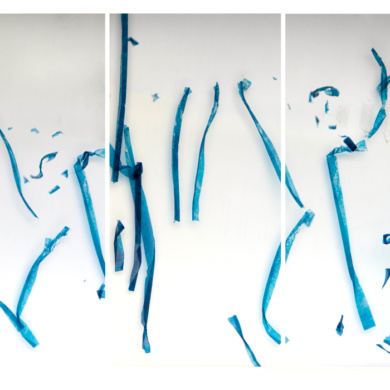

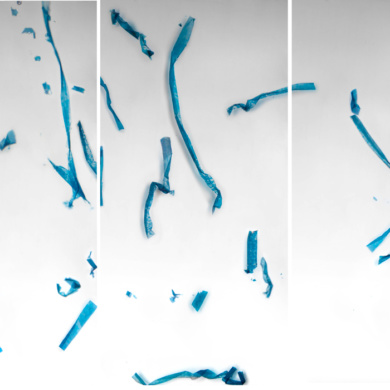

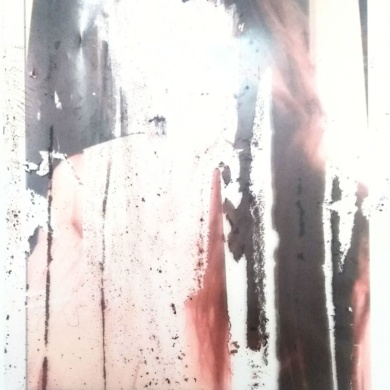

To carry our this project, the results of image searches of the most used hashtags were grouped and subjected to an experimental process of un-development that was different from anything previously done in this series: This led to unique images that were liquid, abstract and fragmentary; a dance of fragmented pieces of information in motion that represent the sum and synthesis of them all. A sort of liquid representation of the algorithms that establish and determine where these images are within the network. By creating a dialogue between these liquid, abstract images –created by the fragments of many other images sharing the same hashtag– and the words used in the hashtags, a new meaning, or rather, a convergence of meanings is created, and this invites us to reflect on this relationship between words and images and on its evolution since the start of the digital revolution and the emergence of social networks.

The liquid images of ”El Monte Perdido” depicted its journey towards its origins and endowed the adjective perdido (lost) –used in the title– with new meaning. Although they still have their name and hashtag, the images in this project have also lost their reference and they appear before our eyes like disconnected particles of memory

Ramond de Carbonnières, the man who reached the top of Monte Perdido in 1802 and discovered its marine origins, wrote, some years later, this sentence about the Pyrenean Pic du Midi that also beautifully describe the feeling of seeing images that are liquid and tagged ”Pic of the Midday”: ”Man’s dwelling is before our eyes; their restlessness remains in our memory, and the weary heart, which has just begun to flourish, still shakes from what is left of the tremor.”

Beatriz de Val